The Dopamine Treadmill

Jan 18, 2025

•

7 min read

•

Skye Gill

The first time I can recall falling to the allures of fantasy was at 8 years old: discovering the massively multiplayer online role-playing game, RuneScape. I would set an alarm 2 hours before school to get up, tiptoe around the house looking for the family laptop, boot it up, connect to AOL's DSL (listen to the dial up sound for a nostalgia hit) and lose myself in Runescape's world.

It's not pretty but it didn't need to be, its mechanics induced a stronger sense of immersion than any graphical interface could. From each swing of my axe to each cast of my fishing rod I would see my skills increase, becoming more powerful with each level. Up to this point in my young life I had only known the constrained routines & curriculum available to children. RuneScape was my first taste of agency, I was free to wander this world and interact with it in any way I so chose, in complete control of my fate. I would feel the impact of every decision with practically immediate effect, flooding my brain with dopamine and hijacking my reward system. I wasn't equipped to see what was happening, let alone put a stop to it. I was hooked. Why?

Dopamine

Dopamine, a neuromodulator, is the chemical behind the brain's reward system. In early bilaterians (ancestors of nematodes), first appearing ~500 million years ago, dopamine primarily acted as a "good-things-are-nearby" signal. It triggered a basic "wanting" state, prompting the animal to search for the source of the reward. In the absence of known rewards the dopamine signal fires when the animal explores, reinforcing reward seeking behaviour. In vertebrates the system evolved by introducing a key innovation: a temporal difference learning signal. This means dopamine no longer simply signals the presence of something good but rather the change in the predicted future reward. As animals learn that certain cues predict rewards, dopamine neurons shift their firing to the moment the cue appears, rather than when the actual reward is received. This allows for more nuanced learning, enabling animals to adjust their behaviour based on expectations and outcomes. The system is crafted, via countless iterations, to reinforce behaviours that improve the likelihood of survival and reproduction of selfish genes.

Rewards

Consider, first, the Stone Age. Imagine you are crouched, poised in the tall grass of the African savannah with a nocked arrow resting on your hand. As you take aim at a grazing impala, your brain surges with dopamine, anticipating the reward of a successful hunt. You shoot and watch with apprehension as the arrow soars through the air before impaling the animal's neck. If the success was a likely one (e.g. highly-skilled hunter, close distance), the dopamine response of hitting the target is far smaller than it would be if the success were unlikely (e.g. long distance, poor visibility). The pathways of your brain have moulded to this successful hunt, priming you to repeat the same action, shooting arrows, in future hunts. Later that night as you sit round the fire, your brain is wisely tuned to other matters, satisfied with your full belly.

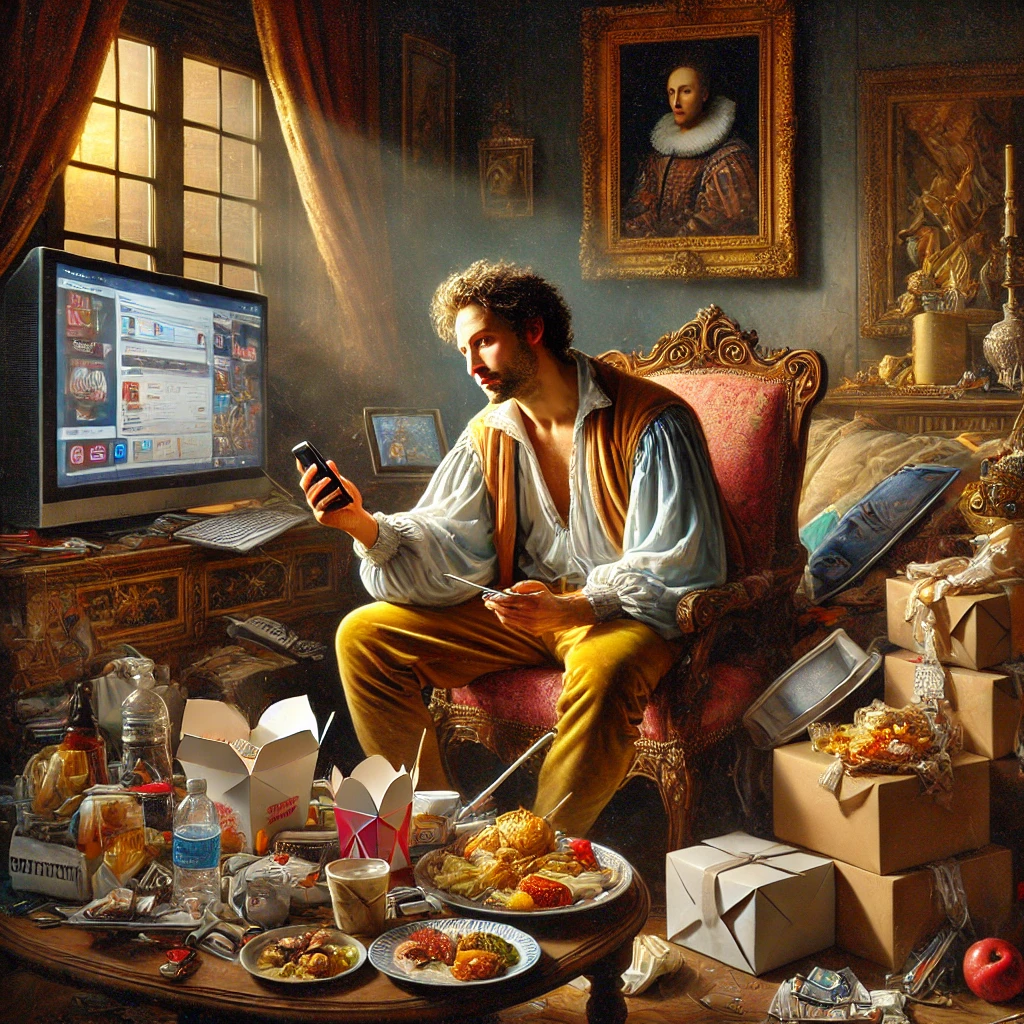

Now, consider the modern world. Basic needs (food, water, shelter, etc.) are taken for granted but our reward systems are anything but dormant. Our desires have changed but the system is as relentless and sustaining as ever. In the absence of known rewards we are drawn to the novel and stimulating, seeking unknown rewards in the novel, or enjoying the stimulation as its own inherently pleasurable reward. It has never been easier to find novel and stimulating ventures than it is in the modern world. Social media is designed to exploit our reward systems. With each scroll, there is a new post, and randomly, after some number of scrolls, something interesting shows up. Even though you might not want to use the social media platform, the behaviour is subconsciously reinforced (by dopamine exploitation), making it harder and harder to stop. The same can be said of gambling. Gambling and social feeds work by hacking into our five-hundred-million-year-old preference for surprise, producing a maladaptive edge case that evolution has not had time to account for. These shallow rewards mimic the satisfaction of a successful hunt but without the lasting fulfilment. This is the escapist treadmill—an endless cycle of distraction and fleeting pleasure.

Escaping Escapism

escapism: the tendency to seek distraction and relief from unpleasant realities, especially by seeking entertainment or engaging in fantasy.

The world is intimidatingly vast and volatile with enough nuance and opportunity to write an infinite number of stories; some good, some poetic, some tragic, but all unique. Every person who came and every person who will be has but one chance to write their's. Growing up burdened by this immense pressure can be paralysing. Frozen by the fear of starting down the wrong path and squandering the one chance you have to write your story, you opt for the seemingly safer option of waiting until you can be certain that the next step you take will be the right one. Until then you are without a purpose, a soulless husk traversing the abyss, latching onto anything stimulating enough to temporarily forget the void. In this state of mind you are subject to all manner of vices. Trapped on the escapist, dopamine fuelled treadmill, you keep walking blinded, waiting your turn for your fateful moment to arrive, for your story to finally open.

I have found myself unwittingly stuck on this treadmill at many points in my life. I started with the anecdote of my 8 year old self because it's the first time I ever got on the treadmill. Now let me tell you about the most recent time. A few months back I was hit from a round of lay-offs at the start-up I was working for. I saw two options ahead of me: the treadmill or the thickets. By this point in my life I'd had enough encounters with the treadmill to avoid its alluring seduction. I took my chances at the thickets. Hacking away, I cleared through the brush by starting to work on a new app idea I had. I was consumed for weeks by this idea, blinded by its potential reward: a life of financial stability. I tinkered away in every free moment I had, spurning any responsibility taking me away from working on my fantasy. A couple weeks in I had made substantial progress but life had other plans, forcing me to take a longer break from the project. On return I was of clearer mind, I asked myself the type of questions I should've started the project with, the obvious ones like, how does this product serve the sort of person who would be interested in it? I immediately came to terms with the flaws of the idea. Cursing myself for not seeing this sooner, I questioned my foolishness. The answer was apparent, I had been ensnared once more, I'd never really had my chance at the thickets. Where did I go wrong?

I had relinquished my agency to the treadmill, disengaging myself from reality to bask in its soothing march to oblivion—mistaking motion for progress. As I reflected on my missteps, I realised that the treadmill itself wasn’t the enemy—it was my relationship with it. There are two types of treadmills: the escapist, that, ironically, traps you in endless cycles of distraction and shallow rewards, and the purposeful, that you build with intention, designed to carry you forward. How can I be sure to choose the latter?

Self-enforced reflection points are necessary to remain with the purposeful. Ask yourself questions about the direction your efforts are taking you on a daily basis. If you are avoiding asking yourself questions about your efforts, the escapist has taken over. Regularly evaluating your actions and intentions ensures your pursuits are aligned with your true, fulfilling goals.